William Drew’s The Last Silent Picture Show really is a treasure of a book. Way too many people get their film history from (admittedly delightful) movies like Singin’ in the Rain, where it’s made to look like the talkie revolution occurred overnight. Most might even assume the American moviegoing public was content to let their silent favorites rot by 1930.

The actual history is far more complicated. In truth, silent films would sometimes get revived for Depression-era audiences, even after all theaters converted to sound. (Not to mention, silent films would still be produced in some Asian and European countries until the mid-1930s.)

Silent comedies were usually revived and given some level of respect– after all, you were supposed to laugh at them. Silent dramas were not so fortunate, at best treated as nostalgia items and at worst openly mocked as outmoded camp. However, there is an interesting case of silent drama revival I just have to share from Drew’s book.

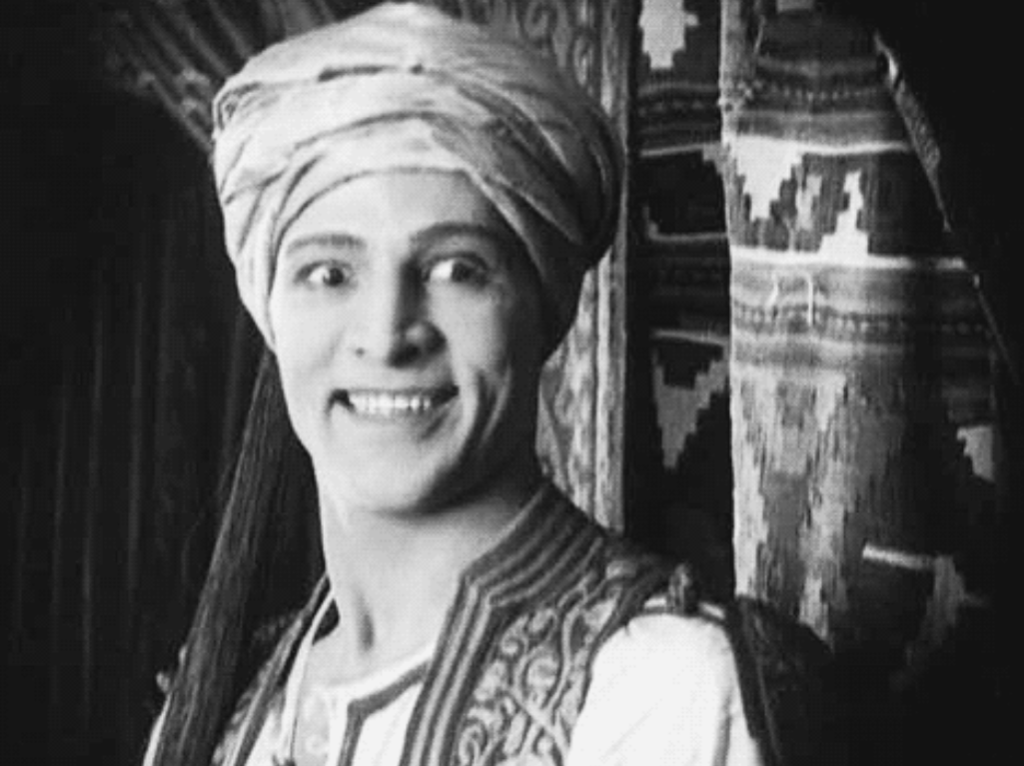

It might surprise some that the two Rudolph Valentino sheik movies were revived throughout the 1930s. The popularity of the original Edith Hull novel and the 1921 movie adaptation had sparked a craze for desert romance in the 1920s, inspiring fashion trends and slang words like “sheik” and “sheba.”

By the time the talkies arrived, this fad mostly died out, though there were a few humorous treatments of the “sheik” theme, such as 1937’s The Sheik Steps Out with Ramon Novarro, a low-budget affair that converted the Hull novel from a racy melodrama to a screwball comedy and replaced the trembling Lady Diana with a wisecracking American heiress.

When Depression-era exhibitors put The Sheik on the bill, it was usually a bid for nostalgia. These showings did draw patrons, though The Sheik was mostly mocked as a “typical” silent film, what with Valentino’s bug-eyed antics and Agnes Ayres’ imitation of a fainting goat. Apparently forgetting that critics in the 1920s had the same issues with the film, it was held up as yet another example of how unquestionably, absolutely superior sound films were in terms of realism (for what that’s worth).

Not everyone reacted this way, of course: Valentino still had a devoted cult fanbase and they did not appreciate snickers from fellow audience members or the accompaniment playing “The Sheik of Araby” to camp up the screening.

While The Sheik might have been enjoyed as a guilty and nostalgic pleasure (not unlike the reaction some have to Twilight these days), The Son of the Sheik was another matter. When a Washington DC theater revived that one in 1938, people rushed for seats.

Yes, you read that right! The “sophisticated” 1930s audience lined around the block to see a silent movie to the point where hundreds of patrons had to be turned away at the box office. Inspired by this success, over five hundred theaters across the United States would revive Son and always to the same bewildered reaction that an “old movie” could be good. Not so bad it’s good, but genuinely well-made, entertaining, and holding its own against current releases. Even skeptical youngsters who had been kids when Valentino died were entranced.

What won over an audience of people hostile to silent films? Comments from both critics and ordinary film-goers emphasized the film’s blend of hot-blooded drama and self-aware humor as the main ingredient for its continued appeal. Unlike the first movie, the sequel is aware it’s dealing in hokum. The actors are all in on the joke while still preserving the sense that vital things are at stake for the characters, a magnificent achievement.

And then there was the silver image of Valentino in his prime. Girls and women too young to have experienced Valentino mania thought he was just as appealing as Hollywood heartthrobs of the day. And of course, those who had loved him long ago felt that fangirlish fervor all over again. As one patron explained, “I loved him, I loved him, I loved him– I still love him.”

If there’s something to be gleaned from this anecdote, it’s that many people– even in the thick of the Golden Age of Hollywood– have turned their noses up at anything older than them or just perceived as “old” in general. This isn’t unique to millennials or Gen Z. Even during the silent era, audiences mocked the stage melodramas of their grandparents’ time.

Everyone thinks themselves more sophisticated then the storytellers who came before them, that their tastes are less “cringey” than the audiences of yesteryear. Sad, but seemingly inevitable. However, there are plenty of treasures from the past in every medium, waiting to be appreciated for those willing to take a chance on anything not made in the past five minutes.

On that note, read Drew’s book! It really is fascinating and filled with other interesting stories like this. In a way, silent films are given more love and attention now than they were immediately after sound arrived.