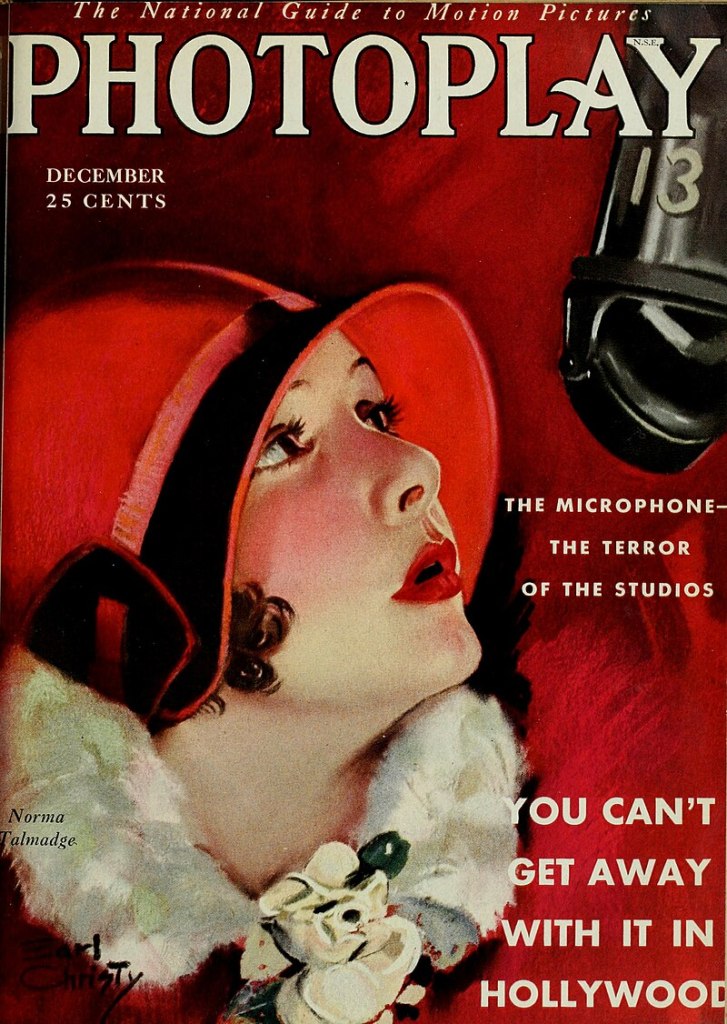

Norma Talmadge is arguably the most elusive of the great silent film stars, even with more of her films becoming available in the last twenty years. In the 1910s and 1920s, her fame rivaled Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford. Her dramatic talents were heralded by the critics, her fashion sense emulated by the public. Her film career was so lucrative she never wanted for money for the rest of her life.

Contrary to the long-standing myth, Talmadge did not have a comical Brooklyn accent a la Lina Lamont. Her first talkie, New York Nights, is competent but forgettable, and her last, Du Barry, Woman of Passion, is pretty bad but Talmadge’s voice certainly is less the problem than a rotten script. It’s easy to say neither film did well because the talkies killed off Talmadge’s appeal, but this does not take into account that her late silents– The Dove and The Woman Disputed— also failed at the box office. Her career peaked in the early 1920s. Perhaps even without the talkie revolution, her star would have faded by 1930.

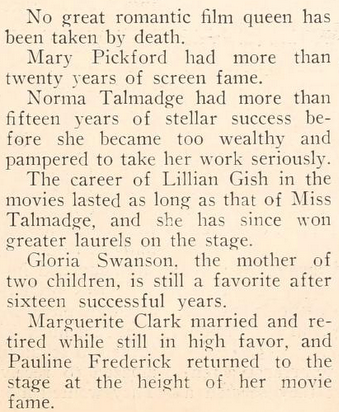

I bring this up because I came across an interesting bit from a 1935 issue of Picture Play magazine while doing unrelated research a few days ago. The article was titled “Men Can’t Take It.” Its hypothesis was that women stars have more longevity with the public than male stars. Later in the piece, the author claims no female romantic idol has ever been taken from the public by a premature death, as opposed to the likes of Wallace Reid or Rudolph Valentino (I guess Florence La Badie doesn’t count?). Listing several silent film actresses and how their careers fared over time, what they have to say about Norma Talmadge is interesting:

No mention of a Brooklyn accent. Apparently, Talmadge’s crown slipped due to her own laziness and declining standards of quality, or so this writer says. I’m a bit skeptical. The Woman Disputed is a handsomely shot melodrama and Talmadge’s performance is good. I see no evidence of phoning it in there. New York Nights and Du Barry are less spectacular, but their problems don’t stem from Talmadge’s acting. If anything, she seems to be trying very hard in both to make the jump to sound.

This is why I wish someone would write a proper, in-depth Talmadge biography. It would be interesting to examine why Talmadge connected so with the public and why they gradually left her behind, even before Jolson told them they “ain’t heard nothing yet.”

Sources:

“Men Can’t Take It” by Madeline Glass, Picture Play (March 1935), https://archive.org/details/pictureplay4143stre/page/n167/mode/2up?q=%22men+can%27t+take+it%22

“Woman disputed: Who was Norma Talmadge and why aren’t more of her films available?” by Greta de Groat, https://web.stanford.edu/~gdegroat/NT/video.htm