Fun fact about me: I read the entire Bible when I was 13 years old. I can’t say it was for any reason beyond a blend of pretentious bibliophilic flexing and boredom.

Growing up in a Catholic household, our Bible included the apocryphal/deuterocanonical books, which are texts considered sacred by some Christian denominations and not others. Among these works is the Book of Judith, the tale of one badass Jewish widow’s quest to save her people from Assyrian invaders. Her home city of Bethulia beseiged, the titular character dresses in her best clothes, marches over to the enemy’s camp, and bats her eyes at Holofernes, the Assyrian general. He falls for her charms and hopes to bed her. Instead, she gets him drunk, chops off his head while he’s passed out, and throws the whole Assyrian camp into confusion, allowing her people to repel their enemies.

Teenage me was OBSESSED with the Book of Judith. It was up there with Final Fantasy X and all my favorite anime series as far as awesome went for my awkward, nerdy self. I re-read it dozens of times. I still love it and I’m hardly the only one. With its intense drama and heady blend of seduction and slaying, the Book of Judith has been catnip for creators throughout the centuries. Painters have reimagined the beheading of Holofernes over and over, sometimes with strong-armed and determined Judiths and other times with sexy, smirking ones. Dramatists and poets have retold the story as well, among them cinematic pioneer DW Griffith.

Judith of Bethulia is significant in Griffith’s oevure because it was final film for the Biograph company. He had been with Biograph since 1908, churning out popular and influential short films. However, as the 1910s dawned, he grew interested in more complex narratives. He started creating longer shorts like his two-part adaptation of Enoch Arden or the half-hour long The Battle at Elderbrush Gulch. Biograph did not share Griffith’s ambitions, contented with the short films that still dominated the market. This would not be the case for long, as features were becoming more common by the early 1910s. Italian epics like Quo Vadis and Cabiria impressed audiences with their detail and scale. Griffith longed to make such an epic of his own and basically defied the Biograph studio bosses to make the four-reel Judith of Bethulia.

It’s easy to mock the Biograph company for their inability to see features as anything but a mere fad, yet they were not the only ones reluctant about longer films. Exhibitors were also wary, fearing a single major feature on the bill would destroy the diversity of the usual multi-short program. Variety was seen as key to the moviegoing experience, since film was often perceived as closer to vaudeville than the “legitimate theater.” The naysayers underestimated how features could be sold as an elevated breed of entertainment. As Eileen Bowser pointed out in her study of this transitional period, “Attending a movie theater where only short films were shown was an everyday affair, but attending a feature was a special event.” That is, a feature film could be an evening’s entertainment, much like a stage production.

With the need for more complicated narratives to fill out the runtime of these features, filmmakers turned to the stage for stories. For his first feature, Griffith chose Thomas Aldrich’s stage adaptation Judith of Bethulia as his subject. The play held personal significance for him since during his theatrical period, he worked in the theater company of none other than Nance O’Neil, a tragedienne christened “the American Bernhardt.” Among O’Neil’s major roles was the lead in Judith. Perhaps choosing Judith as a subject– beyond its potential for battle scenes and historical detail– was Griffith’s way of challenging the theater snobs with the growing power of cinema.

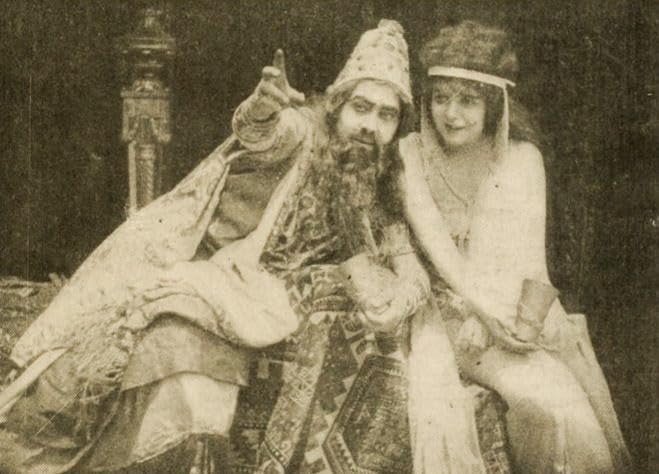

Judith‘s production was a challenge for all involved. Extras were responsible for their own costumes and false beards, and often had to play multiple roles to create the illusion of teeming armies and massive crowds. Sweet’s flimsy costume couldn’t protect her legs when she was riding a horse. The non-imposing Henry B. Walthall was chosen to play the ferocious Holofernes, necessitating cameraman Billy Bitzer to arrange careful camera set-ups to achieve the desired effect. According to Griffith biographer Richard Schickel, the cast and crew bore everything with grace because they were excited to be part of such an epic production.

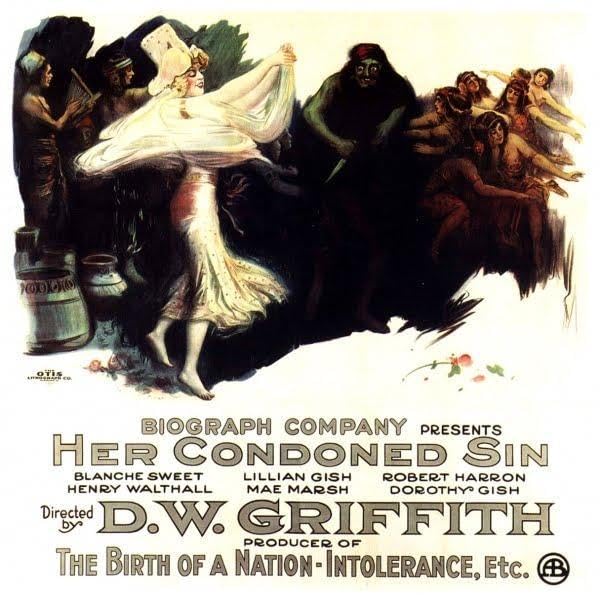

Filming was completed in 1913, but Biograph– alarmed by the hefty $36,000 price tag and Griffith’s insubordination– delayed release for a year. By that point, Griffith had left the company for more artistically fulfilling pastures, taking much of his personnel with him. As Sweet said in an interview for the 1980 Kevin Brownlow documentary Hollywood, the actors and crew’s loyalty was to Griffith, not Biograph. In the end, Biograph would barely outlast Griffith’s departure. By 1916, the company was no longer producing new material and they would close shop in 1918. Coasting off old successes, Biograph would re-release Judith with unused footage and additional intertitles in 1917, rechristening the production with the suggestive title Her Condoned Sin.

Apart from the interesting context, how is the actual film? To be honest, handsome but underwhelming.

When I first saw it early in my cinephilia, I didn’t have much to compare it to in terms of pre-1915 feature films. Having since seen Cabiria and Griffith’s other early features from the 1913-1914 period, it doesn’t stack up as well. I can make a few allowances for it considering this was the first attempt at a feature for Griffith, but I do have issues with the film beyond technical quibbling.

Okay, some good things first. One element that sticks out about Judith is Griffith’s attempt to make Bethulia more than just a movie set plunked in the San Fernando Valley. The opening twenty minutes feature plenty of little scenes showing the townspeople going about their lives. These are not faceless pawns, but likable, vulnerable human beings about to be put in harm’s way by a foreign army. Several subplots are established in these early moments: the most prominent of these minor characters are a young mother with an infant (Lillian Gish) and a pair of young lovers (Mae Marsh and Bobby Harron). While Griffith could not replicate the exact scale of the Italian epics, he wanted to still make the conflict feel grand in scope by creating the illusion of a vibrant community in peril. Not exactly a breakthrough for Griffith– he did much the same in The Battle at Elderbrush Gulch— but still a point in the movie’s favor.

Blanche Sweet is also very good in the lead role. It’s crazy to think she was still in her teens when taking on such a mature part. She exudes the necessary zeal and courage… though the writing undercuts her work just a bit, but more on that later.

The battle sequences are less impressive. They’re overstuffed and messy. It’s impossible to tell what’s going on or who is who. The most emotion one gets from the fight scenes are reaction shots from Judith, teeming with rage and anxiety as she prays for victory. These are my favorite scenes of Judith’s, because they show the ferocity and passion simmering beneath her placid piety. This is the biblical Judith, the one you don’t mess with lest you end up inches shorter.

Unfortunately, this warrior side of Judith evaporates once she goes on her mission to slay Holofernes as the character’s motivation becomes muddied beyond belief. Taking cues from 19th century dramatists who saw the biblical Judith as a heartless monster that needed “womanizing” to be viable onstage, Griffith tries to make Judith more complicated by having her romantically tempted by Holofernes. While I personally don’t care for this idea, it could be done well– if you give Judith credible reasons for wanting some Assyrian hunk or make Holofernes himself a more nuanced character. Griffith doesn’t do either.

Let’s examine how Griffith establishes his heroine’s characterization. Judith is a devout Jew and a maternal figure for her people. Her love of them is so fierce that she risks her life by going into enemy territory to seduce and kill the enemy leader. So far, so good.

But wait! When Judith meets Holofernes and he gives her free stuff (a tent, a eunuch to wait on her every need), he “becomes noble in her eyes.”

Noble? Giving hot women tents and a eunuch in a towel suddenly makes you “noble”? In what universe?

It would be one thing if Holofernes actually did something actually noble like, I don’t know, show mercy, even if only to a single person, suggesting some capacity for compassion. Or if he showed any remorse for his ruthless actions against Bethulia’s population. Or if he handed out kittens to an orphanage. I don’t know. I’m not an expert in the realm of romance, but surely a religiously devout woman who’s seen babies starving due to Holofernes’ orders wouldn’t have her head turned by a free tent.

We get a lot of scenes of Judith wringing her hands over this incredible dilemma, intercut with Holofernes no longer able to pay attention to his mini-court of sexy dancers. There isn’t much chemistry between Sweet and Wathall, and Judith has no legitimate reason to “love” Holofernes, so much of the movie just drags. It’s true Griffith favored the broad strokes of melodrama even in his artier work, but here, there’s nothing compelling about any of the drama, even in the realm of potboiler passion. The feature never justifies its length, coming off as a two-reeler stretched to the breaking point.

Part of me fears I’m being too harsh. This was an early attempt at a feature film. That it’s an awkward effort is to be expected. To quote Richard Schickel, Judith represents “a noble ambition, not a fully realized one.” Or maybe I’m just too much of a Judith fangirl to be satisfied.

My meh view of the film tends to be shared by modern film geeks, but in its day, critics were impressed by Judith of Bethulia. It was a milestone in American feature filmmaking and contemporary audience response reflects that. One anecdote in particular always sticks out to me when I think about this film. Griffith’s old colleague Nance O’Neil came by when the cast and crew were filming interior scenes in Judith’s house. Blanche Sweet was about to do her big mourning scene in sackcloth and ashes. Griffith offered to show O’Neil what moviemaking was like and before the cameras started rolling, he whispered to Sweet, “Show her.” That is, show her the movies are as legitimate a form of art as the theater.

Judith of Bethulia was a major part of the collective effort of Edwardian era filmmakers to prove that and then some. While everyone involved would move onto greener pastures, it was a necessary transitional film and it remains an influential one, even if I prefer my Judith adaptations without Judith/Holofernes love stories in them.

Sources:

Adventures with DW Griffith by Karl Brown

DW Griffith: An American Life by Richard Schickel

Hollywood: A Celebration of the American Silent Film (dir. Kevin Brownlow and David, Gil, 1980)

“Judith of Bethulia,” https://www.silentera.com/PSFL/data/J/JudithOfBethulia1914.html

The Transformation of Cinema, 1907-1915 by Eileen Bowser