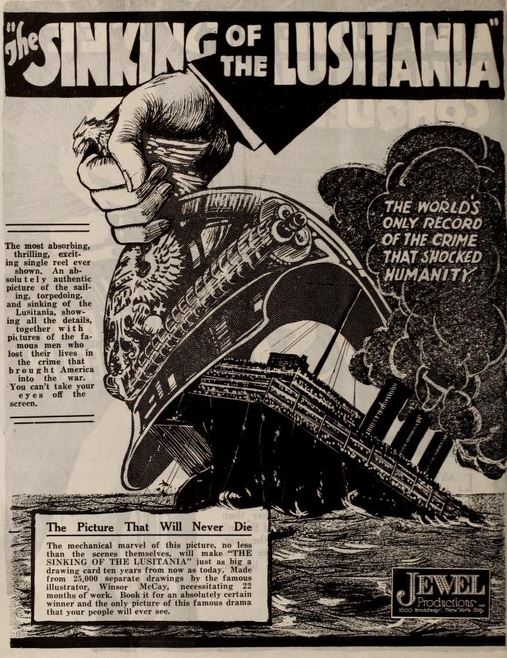

Animation pioneer Winsor McCay was a man of many talents. Before 1920, McCay would work as an illustrator, comic book creator, political cartoonist, vaudevillian, and filmmaker. It is as a filmmaker that he is most remembered today, particularly for his 1915 short Gertie the Dinosaur. However, his ambitions went beyond what most thought possible for animation as an art form. Considering we still live in an era where the mainstream sees animation as little more than an electric babysitter, the scope of those ambitions remains impressive.

In 1915, McCay was enraged by the fate of the Lusitania, an English commercial liner torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat. Almost 1,200 people died in the disaster, including American civilians. The sinking would not catapult the US into the Great War, but it did establish angry feelings towards Imperial Germany and would be a major contributing factor when the country did enter the conflict in 1917. In the meantime, the event inspired McCay to create a harrowing work that would allow people to see the ship’s final moments.

The Sinking of the Lusitania is McCay’s masterpiece and representative of a road long untaken by the American animation industry at large. To this day, mainstream American animation is associated with two genres: fantasy (usually for children) or comedy (usually for children or frat boys). The Sinking of the Lusitania is neither. McCay set out to recreate the infamous sinking in an expressive but realistic style, essentially creating an animated documentary.

The film was a labor of love for McCay. He funded it himself and worked on it in his free time for a period of twenty-two months. While the film never made a profit for its creator, it was heavily admired by both audiences and animation professionals at the time.

Early cartoons tend to be pigeonholed as visually simplistic, but this is certainly not the case for The Sinking of the Lusitania. Here, the sheer amount of detail is staggering. Just look at the virtuosity of the shot in which the first torpedo speeds through the water, fish ducking out of its path—or look at the long shot of the sinking ship and the tiny figures of individual human beings jumping from the vessel. These are scenes that would have been either impossible or difficult to achieve in a live-action movie during that time.

Just compare this film to the 1917 Mary Pickford vehicle The Little American, which features a thinly disguised depiction of the Lusitania’s sinking. The animated film is far more chilling and dynamic.

McCay never shies away from the horror of the sinking. The short’s most striking moments feature the victims of the attack trying to keep their heads above the waves, their miserable faces resembling skulls. Most heart-wrenching of all is the shot of a mother thrusting her baby above the water, desperately trying to ensure its survival before they are both pulled down.

Propaganda is perhaps the more appropriate descriptor for this film than documentary. Released during the war itself, The Sinking of the Lusitania brims with outrage against Imperial Germany, reflecting popular sentiment during this time. Anti-German feelings grew to a lethal fever pitch once the country entered the war in 1917, unfortunately extending even to German-American communities. The “Huns” were depicted as freedom-hating, baby-killing monsters who needed to be stopped at all costs. The final intertitle is chilling in its echoing of this national fervor: “The man who fired the shot was decorated for it by the Kaiser! AND YET THEY TELL US NOT TO HATE THE HUN.”

In recent years, some elements of the film’s depiction of the sinking have been debunked. Most significantly, it was revealed in 1982 that the ship was carrying military ammunition. Of course, that does not make the loss of innocent life any less tragic. As animation historian John Canemaker observed, even if these facts had been known in 1915, they likely would not have had much impact on the emotions surging throughout the US at the time.

Removed from the fear-soaked, enraged environment in which it was conceived, The Sinking of the Lusitania remains compelling, its combination of gorgeous animation with raw emotions elevating it from mere historical curio to disturbing work of art. Canemaker once said the film’s dramatic power was not equaled in American animation for many years. I would have to agree.

Sources:

Winsor McCay by John Canemaker