For the first entry in my new Short of the Month series, I’m going to gush over what might be my favorite short film of the 1910s: Suspense, directed by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley.

If you’ve never seen Suspense, then I recommend watching the short in question before reading on. You can watch the short below:

This taut home invasion thriller is a gem of early cinema. The plot’s basic DNA– a woman left alone in her home is menaced by an outside force– would be shared by many movies to follow, from Sorry, Wrong Number to Panic Room. Running only ten minutes, Suspense keeps its story simple: a housewife and her child are threatened by a malicious tramp in their isolated house, the phone line cut and help far away. Can they be rescued in time?

Though thoroughly cinematic, Suspense was inspired by the theater. The chief influence is a grim 1902 French play titled At the Telephone, which was performed at the Theatre du Grand Guignol in Paris and at the Garrick Theatre in New York. Unlike the later works that would be inspired by it, the original story ends on a dark note as the husband hears his frightened wife and child being murdered by intruders over the telephone.

Though little known today, At the Telephone was quite the influential thriller. In its day, it was adapted into a 1904 French film. The story also inspired Griffith’s 1909 The Lonely Villa, which concludes with a just-in-the-nick-of-time rescue by the victim’s husband. Suspense is another variation on this story, but its cinematography and energy elevate it above its predecessors as a work of cinema.

If you seriously think all early films were theatrical and static affairs, Suspense will shock you to your core with its dynamic camera angles and groundbreaking use of split screen. These artistic choices are more than trendy stylistic flourishes or empty attempts at standing out. They serve the story and the movie’s raison d’etre: thrusting the audience into a state of dread and anxiety.

Take the early scene in which the maid, driven crazy by the isolation of the remote house, exits the front door. Instead of opting for a static frontal shot much the way such a moment would be viewed on a stage, Weber and Smalley place the camera at a high angle, gazing down at the maid from the top of the porch. The high angle strikes an ominous note, an almost God’s eye perspective.

The early moments also create a sense of voyeurism and privacy being invaded. Before leaving her bitter resignation letter, the maid peeks through a keyhole to watch the guileless wife interacting with her baby. Later, the tramp gazes in on the domestic scene through a window. As with later home invasion films, the security of the domestic space is compromised by criminal onlookers. The wife and her child are like goldfish in a bowl being eyed by a hungry cat.

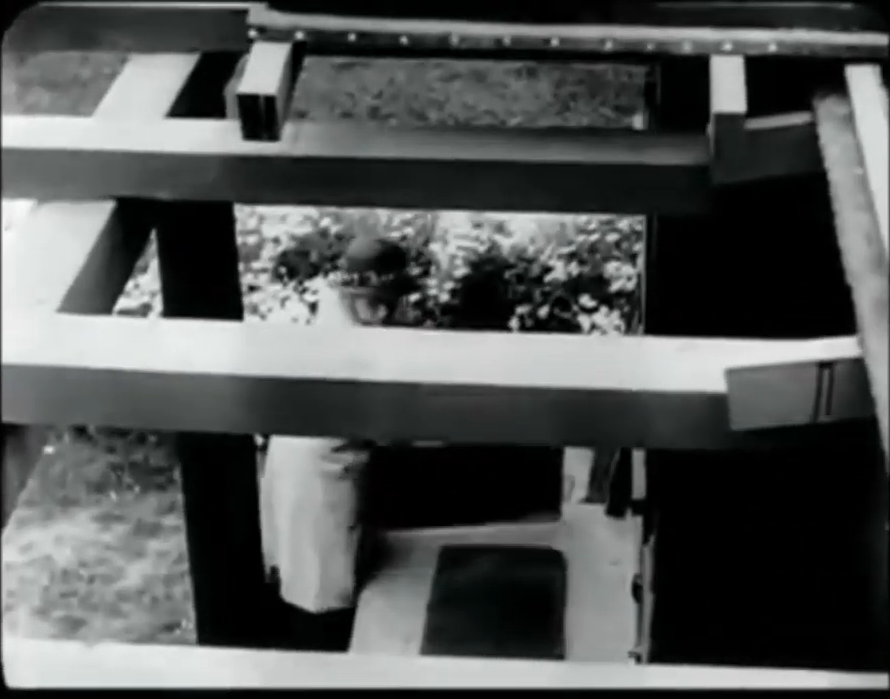

The split screen in particular is used so well. Suspense was not the first to use the technique, but it might have been the first to split the screen three ways. Watching the film again, I was reminded of the vogue for complicated split screens in 1960s crime movies like The Boston Strangler and The Thomas Crown Affair. Those films use split screens to create suspense or to evoke the complexities of a criminal plot.

Suspense uses the device in the same vein as those movies in which we see at once the victim in her home, her husband far away at work, and the intruder as he finds the house key under the mat.

While Suspense lacks the overt violence audiences expect from home invasion movies today, the tramp is still a chilling character. His vacant expressions evoke the impassivity of wild animals and he is the one character in the short to not receive a single dialogue intertitle. It’s interesting how his exact intentions regarding the wife are never laid out. Does he just want to kill her or does he have more sinister intentions as well? That the film never tells us makes his entry into the bedroom all the more disturbing.

While DW Griffith is often marked as the nickelodeon era’s Master of Suspense with his races to the rescues and cross-cutting, Weber and Smalley go to show how Griffith was hardly the only pioneer in town. I dare to say they even out-Griffithed Griffith with this one! Suspense is a great introduction to early cinematic dramas: short enough to not tax a modern viewer uninitiated to the slower pace of older movies and still intense enough to quicken the pulse.

Sources:

An English translation of At the Telephone by Andre De Lorde

https://www.ibdb.com/broadway-production/at-the-telephone–theres-many-a-slip-5620

Firstly, the print of this film is immaculate, especially having been made in 1913 and being over a century old, most films of this period have considerable age, this one doesn’t. Visually this is indeed very impressive, especially the camera angles as you’ve mentioned. I’d never heard of Lois Weber before, but she sounds like one of many great early filmmakers who’s just finally being reappreciated. A very simple and effective little short.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lois Weber is indeed one of the great early filmmakers. Suspense is a little bit of an outlier in her general filmography since many of her films were socially conscious dramas tackling the big, controversial issues of the day: class differences, birth control, poverty, and moral hypocrisy, just to name a few. I would highly recommend seeking out her work, particularly the 1915 feature Hypocrites.

The wonderful Silentology blog also has a great article on Weber’s life and films, if you want to learn more about this great director. She was astonishing and I’m glad she’s getting more of her due.

https://silentology.wordpress.com/2018/01/25/the-muse-of-the-reel-the-pioneering-work-of-director-lois-weber/

LikeLiked by 1 person